Print This Article

Opioid Task Force - CPE Opportunity!

Emergency Department (ED) Dispensing of Naloxone Take-Home Kits

Feature Article

by Marc McDowell, PharmD, BCPS; Emergency Medicine Clinical Specialist; Emergency Medicine PGY-2 Residency Director; Advocate Christ Medical Center; Oak Lawn, IL

Introduction, Purpose, and Goals of the Program

The opioid crisis is a public health epidemic without boundaries. The devastation brought by the misuse of prescription or illicitly-obtained opioids is unparalleled within this generation. Opioid-related deaths rose to a record 47,600 in 2017 in the United States, constituting a 600% increase in less than two decades.1 In 2018, over 72,000 people in North America died of opioid-related overdoses. Approximately 2,200 of these fatalities occurred in Illinois.2 The deaths attributable to opioid misuse are twice as high as all Chicagoland homicides or motor vehicle fatalities during the same year.3

Unfortunately, the case fatality rate is expected to climb exponentially over the coming decade. It is currently estimated that for every fatal overdose, 30 non-fatal overdoses will occur.4 By this approximation, Illinois’ citizens suffered approximately 66,000 opioid overdoses in the past calendar year. Although the disease state of opioid use disorder (OUD) is multifactorial, initial opioid exposure is one of the major contributors to this epidemic.5 Approximately 16% of patients receiving more than a one-week supply of opioids and 6% receiving a one-day supply reported continued use after one year. For this reason, a focus on safe prescribing practices is necessary.

In addition to the tragic loss of life and the burden to the healthcare system, medical care costs are another victim of this crisis. Emergency Department (ED) visits related to opioid overdose continues to rise with a 65.5% increase seen from 2016 to 2017.The mean hospital cost for an opioid overdose treated solely in the ED is $504, but this increases drastically to $11,731 for an inpatient admission. This cost climbs to over $20,000 if a stay in intensive care is required.6 This introduces a large financial stressor on healthcare systems and may limit their ability to provide other necessary services to the community.

Opioid Use Disorder (OUD) is often linked with the socioeconomically and functionally marginalized populations. These patients often have poorer access to primary medical care and may rely on the ED as their main point of contact for health care. This creates a distinct opportunity for healthcare professionals within the ED to intervene and address the current opioid epidemic. Staggeringly, after being discharged from an ED for an opioid overdose 1% of patients die within a month, and over five percent die within one year.7 ED prescribers and pharmacists are afforded the unique ability to identify those suffering and those at risk of suffering from this disease. From this vantage point, a number of harm reduction strategies, initiatives, and programs can be implemented to effectively assist those suffering with this disease.

Recently, dispensing naloxone to the general population from harm reduction agencies has begun to take root in at-risk communities. These programs are endorsed by several professional medical organizations for high-risk patients.8 Specifically, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention endorses the creation, utilization, and expansion of naloxone distribution programs. Naloxone, a potent mu-opioid receptor reversal agent, is frequently administered by pre-hospital emergency medical services (EMS), hospital staff, and more recently the general public. A growing body of evidence has demonstrated the feasibility and success of naloxone distribution programs.9 Research by Abouk et al demonstrated that mortality can be directly decreased by dispensing naloxone to at-risk patients being discharged from a health system or ED.10,11

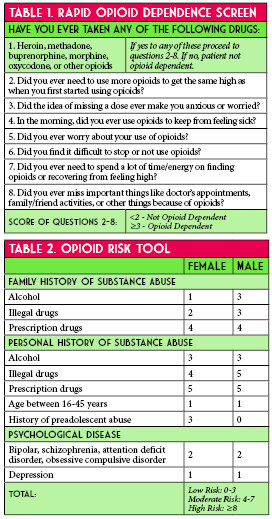

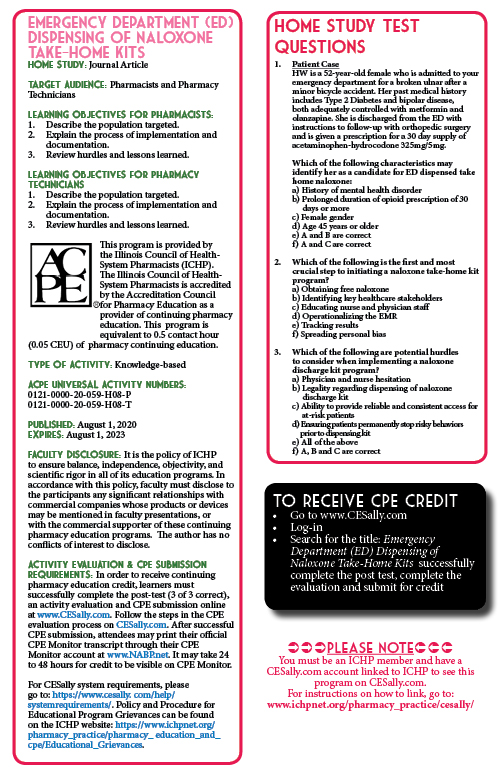

Appropriate selection of at-risk patients remains vital in combating this epidemic. These patients present along a continuous and challenging spectrum. Utilizing an appropriate screening tool is paramount to capturing and assisting all instances of potential OUD. This ranges from the candidate who presents to the ED via emergency medicine services for a repeated life-threatening opioid overdose to more subtle yet just as dangerous scenarios. For example, a patient with underlying mental illness presenting with a moderate to major traumatic injury may be in a precarious position if they require concomitant atypical antipsychotics and opioid therapy for analgesia.12 The adoption of a tool to screen patients for opioid dependence may be a logical approach to ensure safe prescribing practices. The Rapid Opioid Dependence Screen (RODS) is an 8-item validated tool used to assist and measure opioid dependence (Table 1).13 The ease of use of RODS makes it an ideal instrument for assessing current dependence in the ED setting. However, determining active dependence and potential for opioid abuse are similar but distinct. The Opioid Risk Tool (ORT) is a brief, self-reportable screening tool designed for use with adult patients in primary care settings (Table 2).14 Depending on the practice setting and patient population, identifying and using the appropriate questionnaire or combination thereof can broaden a program’s impact on potential OUD patients.

Unfortunately, many patients with opioid use disorder do not seek appropriate resources prior to their first overdose. Recent literature suggests that only 18% of naloxone prescriptions are filled and picked up after discharge leaving many patients untreated.15 As previously mentioned, the ED is a major touch point in the opioid battle. Given the prevalence of unmet substance abuse needs among patients in the ED and the increasing frequency of drug-related visits the ED acts as a vital link to appropriate medical care for at-risk patients. In September of 2017, the Illinois Department of Public Health (IDPH) issued a standing order authorizing pharmacists to dispense naloxone for reversing potential opioid overdoses without a direct prescription.

Our health-system recognized that pharmacists and pharmacy technicians were poised to translate these data into a tangible and successful program. Our goal was the implementation of a systematic and comprehensive process involving free distribution of naloxone from the ED. We aimed to accomplish this in a simple and cost-efficient manner to provide a potentially lifesaving intervention to an at-risk demographic.

Design and Implementation

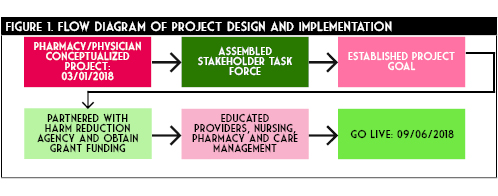

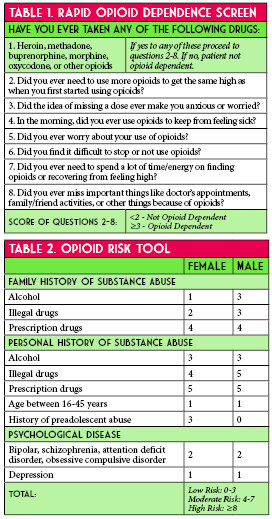

In May 2018 an interdisciplinary task force of pharmacists and physicians met to address the issue of local OUD in the community (Figure 1). The discharge naloxone program was conceptualized in late May. One of the initial steps of the task force was to identify key stakeholders needed to implement a successful ED naloxone discharge kit process. Providers from emergency medicine, pain management, pediatrics, information technology pharmacy, behavioral health, inpatient substance withdrawal unit, and ED nursing were jointly collaborated to leverage their expertise and clinical experience. Goals for this team were to provide take-home naloxone, at no cost, to patients at risk of OUD or their family members.

Subsequently, supply of medications and necessary supplies were addressed. In partnership with a local community harm reduction agency, the pharmacy department designed and obtained naloxone kits via combination of donation and grant contributions. Each kit contained 0.4mg/1ml naloxone vials, small three mL syringes, and intramuscular needles in triplicate, as well as community substance abuse outreach information. Kits were contained in a small protect from light bag large enough to affix a prescription label. Kits were stored in central pharmacy.

The team developed several documents, training pathways, and poster materials to aid in the education of all parties involved with this project. Primarily the documents focused on the availability of the take-home kit, patient eligibility for a kit, and work-flow process to obtain a kit. These were posted throughout the ED in patient rooms, physician charting areas, nurse workspaces, and the ED pharmacy work station. Additionally, a nine minute training video was shared among all staff detailing the importance of OUD and the effectiveness of outpatient naloxone. Development, training, and procurement of medication occurred over the next four months.

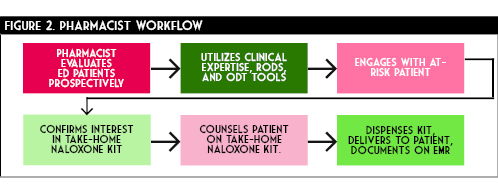

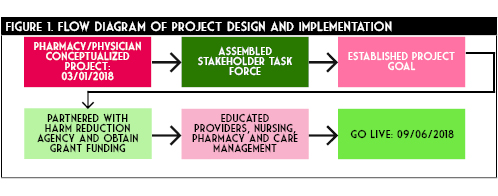

Optimal workflow was operationalized with an ED pharmacist identifying a potential patient at risk of OUD and outpatient opioid overdose (Figure 2). This was done by assessing a RODS and ODT score, evaluating patients with home regimens on abnormally large doses or long durations of opioids, those with history a of OUD, those presenting to the ED for an acute opioid overdose, as well as family or friends of those presenting with any of the above patients. The ED pharmacist clinical acumen was used to determine abnormal doses and duration of opioid outpatient prescriptions. The pharmacist would then engage in open dialogue with the at-risk patient and, if appropriate, their caregiver, family, or friend regarding OUD and the danger of an opioid overdose. This conversation would offer the take-home naloxone kit at no charge. Additionally the ED pharmacist would provide counseling regarding naloxone or any other pertinent patient medications. If the patient was interested in receiving a kit, the pharmacist would then share the same nine minute training video with the patient. This video detailed the ideal process for utilization of the naloxone kit. In a stepwise fashion the video reviewed when to administer naloxone, how to draw up the medication from the vial into a syringe and administer as an intramuscular injection, how often to re-administer, and when to call 911. The ED pharmacist would then enter the order to dispense a kit in the electronic medical record and ensure the kit delivery to the patient. The pharmacist would then document in the medical record that the patient received the kit. All dispensing is reported to the Illinois Prescription Monitoring Program in compliance with Illinois state law.

Preliminary Results

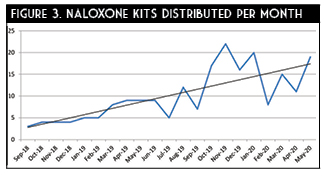

Project go-live was approximately six months after conceptualization on September 6th, 2018. A total of 212 kits, which included 636 doses of naloxone were distributed in the 20 months since initiation (Figure 3). Some trends are observed from this data. The initial months of the program utilization was relatively low, averaging only five kits dispensed per month. Over the course of the subsequent 15 months a drastic increase in distribution occurred. This is evidenced by over 60% of all kits being dispensed in the final six months of data collection. This demonstrates an exponential growth of the program. Expanded utilization is attributable to multiple factors.

Initial hesitation by physicians to recommend naloxone at discharge was anecdotally reported. However, as the program progressed, familiarity, awareness, and comfort seemed to increase for all members within the department. Additionally, ED pharmacy coverage expanded during the final months of data collection. This allowed our team to capture more of these at-risk patients and increase overall distribution. On average, our ED treats approximately 15 opioid overdose patients monthly. By this estimation we were able to capture and intervene in over 70% of this population. Based on the upward trend of kit distribution and the spread of the epidemic, we anticipate that this program will continue to grow in the coming months.

Unfortunately, due to the nature of the disease state and pharmacologic intervention, obtaining objective patient-centered outcomes is difficult. Measuring kit utilization, lives saved, reduced utilization of EMS, admissions, and intensive care needs is cumbersome, if not impossible to quantify. However, the costs associated with each of those components of the healthcare system are substantially higher compared to three doses of naloxone.

Hurdles and Lessons Learned

Despite the eventual success of this program, several barriers challenged the key stakeholders during development. Provider and administrator concern regarding the legal liability surrounding the take-home

kit was an initial challenge. Educating stakeholders and discussing the full extent of the IDPH standing order alleviated this hesitation. An additional layer of complexity was realized regarding state pharmacy law concerning outpatient medication dispensing from an inpatient hospital setting. Specifically, if this kit were dispensed from the ED, what labeling would be appropriate or necessary? A concise review of Illinois State Law and Acts by a recent peer-reviewed publication by Eswaran and colleagues is an excellent tool for navigating this issue.16 This was overcome by ensuring NDC, LOT, and expiration dates were all tracked by the inpatient pharmacy department. Similar labels utilized for sexual assault post-exposure prophylaxis were affixed to the physical kit.

Physician and nursing resistance was also a preliminary challenge. This was in part due to lack of familiarity with a harms reduction strategy and a fear of encouraging unhealthy behaviors. With further education and time, providers witnessed not only the benefit of such a program by their peers who were utilizing the kits, but also the gratitude from at-risk patients. The increase in dispensing rates is evidence that adoption of the program became more widespread over time.

Funding and securing supplies were initial concerns for the program as well. As mentioned, providing the kits at no charge was one of our primary goals. It was not feasible to bill the insurance for the dispensed product considering the setting of the ED. Thus our options were donating inpatient supply as charity care, obtaining outside funding via grants or donations, or utilizing our 340B program. Ultimately, we were able to obtain assistance from a local harm-reduction organization. However close consideration was given to charity care as the cost-benefit of saving just one ED visit would have financed the program for well over a year.

While reliance on the ED pharmacist to assess, consent, counsel, and obtain the kit for the patient reinforced our professions aptitude and necessity, it also proved a barrier. Due to limited and variable ED pharmacist coverage undoubtedly some candidates for the kit fell through the cracks. Although our services were available the majority of hours in the day, seven days a week, access to naloxone kits for an at-risk patients should not be impacted by a lack of resources. Opportunities for improvement include providing education for nursing and physician staff to duplicate these responsibilities. Pharmacy technicians served a vital role in this program as well. They not only delivered kits to the ED but also manually batched the kits.

summary and future goals

Our novel program has impacted the lives of the patients as well as their families. By dispensing 212 kits in a relatively brief amount of time, our team of pharmacists have elevated the quality of life in the at-risk community in our area at no additional cost to the institution. This clearly demonstrates that clinical pharmacists are effective leaders and stewards in the fight against the opioid epidemic. Pharmacy technicians are important to the success of such programs; assisting with kit creation and timely distribution being two essential tasks they are able to facilitate.

Currently, the naloxone discharge kit program is being expanded to the inpatient areas of our institution. This will help capture at-risk patients who are directly admitted to the hospital who may have bypassed the ED or those who are diagnosed with OUD later in their hospitalization. There is a strong need for appropriate treatment of opioid use disorder among our patients admitted to the hospital for other medical reasons. By having this kit and education available to inpatient participants, we can address this disease state in a cost-effective and proactive manner. In the future we hope to expand this program across several other institutions in our healthcare system to offer a new standard of care within our shared communities.

Sustainability is key for our service to continue to be offered to our at-risk community. Continuing to secure grant funding is paramount to our success. We are currently aggressively tracking metrics on patients with OUD who present to the ED and how frequently they participate in the program and obtain appropriate follow-up. ■

_____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

References

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. World Drug Report 2017. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/press/releases/2017/June/world-drug-report-2017_-29-5-million-people-globally-suffer-from-drug-use-disorders--opioids-the-most-harmful.html (accessed 2020 Jun 23).

- Illinois General Assembly. Cannabis Regulation & Tax Act Springfield, IL. 2019. http://www.ilga.gov/legislation/ilcs/ilcs5.asp?ActID=3992&ChapterID=35 (accessed 2020 Jun 23).

- Allen JH, de Moore GM, Heddle R, Twartz JC. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: cyclical hyperemesis in association with chronic cannabis use. Gut. 2004; 53: 1566-1570.

- Richards JR. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Pathophysiology and Treatment in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. 2018; 54(3): 354-363.

- Simonetto DA, Oxentenko AS, Herman ML, Szostek JH. Cannabinoid hyperemesis: a case of 98 patients. Mayo Clin Proc. 2012; 87(2): 114-119.

- Sorenson CJ, DeSanto K, Borgelt L, et al. Cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome: diagnosis, pathophysiology, and treatment – a systematic review. J Med Toxicol. 2017; 13(1): 71-87.

- Hendren G, Aponte-Feliciano A, Kovac A. Safety and efficacy of commonly used antiemetics. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2015; 11: 1753-67.

- Abalo R, Vera G, Lopez-Perez AE, Martinez-Villaluenga M, Martin-Fontelles MMI. The gastrointestinal pharmacology of cannabionoids: focus on motility. Pharmacology. 2012; 90(1-2): 1-10.

- Carvalho AF, Van Bockstaele EJ. Cannabinoid modulation of noradrenergic circuits: implications for psychiatric disorders. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2012; 38: 59-67.

- Lapoint J, Meyer S, Yu CK, Koenig KL, Lev R, Thihalolipavan S, Staats K, Kahn CA. Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome: Public Health Implications and a Novel Model Treatment Guideline. West J Emerg Med. 2018; 19(2): 380-386.

- Roman F, Llorens P, Burillo-Putze G. Topical capsaicin cream in the treatment for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome [in Spanish]. Med Clin (Barc). 2016; 147(11): 517-518.

- Moon AM, Buckley SA, Mark NM. Successful treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome with topical capsaicin. ACG Case Rep J. 2018; 5:e3.

- Sharma U. Cannabis hyperemesis syndrome. BMJ Case Rep. 2018. doi:10.1136/bcr-2018-226524.

- Dezieck L, Hafez Z, Conicella A, et al. Resolution of cannabis hyperemesis syndrome with topical capsaicin in the emergency department: a case series. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2017; 55: 908-913.

- Graham J, Barberio M, Wang GS. Capsaicin cream for treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome in adolescents: a case series. Pediatrics. 2017; 140: e20163795.

- McCloskey K, Goldberger D, Rajasimhan S, McKeever R, Vearrier D. Use of topical capsaicin cream for the treatment of cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome. Clin Toxicol. 2017; 55: 828-829.

- Wagner S, McLaughlin J, Hoppe J, Zuckerman M, Schwarz K. Efficacy and safety of topical capsaicin for cannabinoid hyperemesis syndrome in the emergency department. Clin Toxicol. 2018; 56: 982.

- Zostrix [package insert]. Ann Arbor, MI: Akron Consumer Health; 2020.

____________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________