Print This Article

Educational Affairs

Clinical Considerations For The Use Of Glucagon-Like Peptide-1 Receptor Agonists and Sodium-Glucose Cotransporter-2 Inhibitors In Diabetes Mellitus

by Henry Okoroike, PharmD Candidate, Class of 2020, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy; Liz Van Dril, PharmD, BCPS, BCACP, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy

In December 2019, the American Diabetes Association (ADA) released updated 2020 Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes.1 The recently updated pharmacologic treatment algorithm for people with type 2 diabetes supports the early use of a glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist (GLP-1 RA) or a sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 (SGLT-2) inhibitor after metformin. The ADA recommends considering important comorbidities such as atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), chronic kidney disease (CKD), and heart failure when selecting a second pharmacological agent, and in certain high-risk persons with diabetes the decision to use a GLP-1 RA or SGLT-2 inhibitor to reduce cardiovascular risk or slow renal disease progression should be made without regard to baseline hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) or HbA1c target. This recommendation is based on recent findings from cardiovascular outcomes trials with these therapies. Understanding and applying the updated recommendations provides opportunities to improve patient care and the potential to educate patients and other healthcare practitioners about how to improve diabetes-related outcomes beyond HbA1c-lowering. This article includes clinical pearls to help guide decision-making with regard to GLP-1 RAs and SGLT-2 inhibitors and how to communicate these recommendations to other members of the healthcare team.

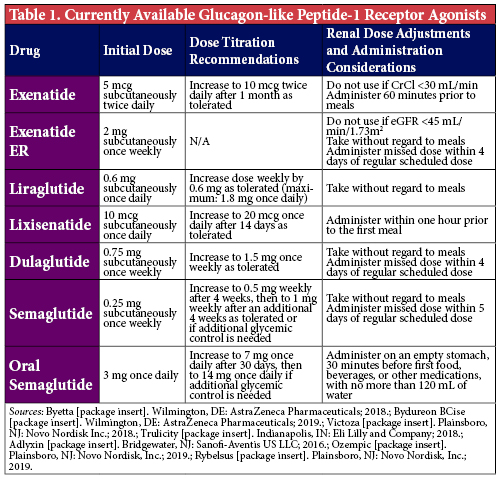

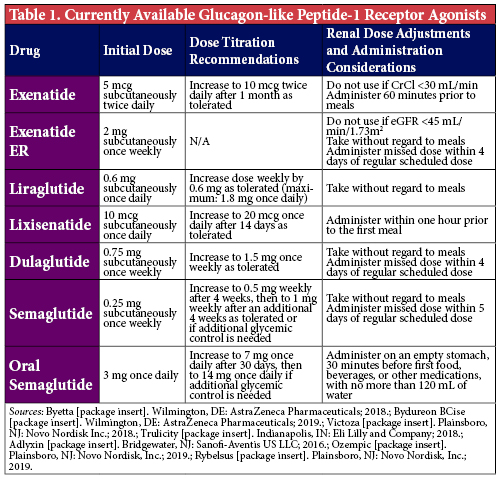

First, understanding the mechanism of action of these agents will be extremely helpful when communicating both the benefits and risks of therapy to patients and providers. The GLP-1 RAs (Table 1) are synthetic analogs of human GLP-1, an incretin hormone, that bind to GLP-1 receptors. These analogs work by enhancing glucose-dependent insulin secretion, decreasing glucagon secretion - and therefore hepatic glucose production - and slowing gastric emptying to increase satiety and promote weight loss. The main adverse effects associated with GLP-1 RAs are gastrointestinal, with nausea being the most common. This effect is a natural byproduct of their ability to slow gastric emptying, which typically results in patients feeling fuller for longer periods of time. However, this may predispose patients who are accustomed to eating larger meals very quickly to an increased risk of overeating, which can precipitate nausea and even vomiting in severe cases. To mitigate the risk of gastrointestinal effects, these agents are typically titrated slowly (e.g., after 1-2 weeks for shorter-acting agents, and after 1 month for once-weekly agents) up to their maximum tolerated doses. Tolerability will also improve if patients are counseled to initially consume their meals very slowly to avoid overeating, or to consider smaller, more frequent meals as opposed to larger meals as the body adjusts to the delayed gastric emptying. While initially bothersome to some patients, this adverse effect is also the mechanism behind the associated weight loss seen with GLP-1 RAs, as it curbs patients’ appetites and promotes decreased caloric consumption.

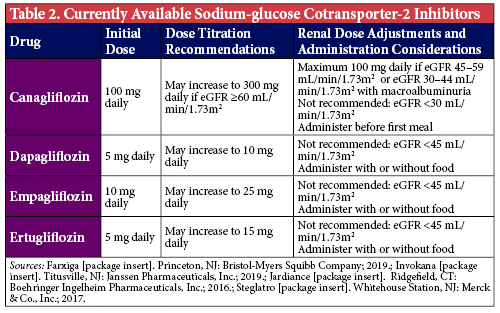

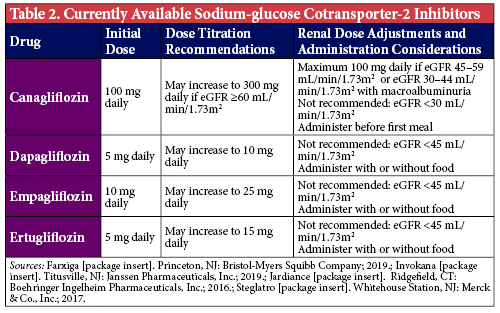

The SGLT-2 inhibitors (Table 2) block glucose reabsorption in the proximal renal tubule to increase urinary glucose excretion. As 90% of all glucose is reabsorbed via SGLT-2 receptors, blocking this cotransporter provides a novel way to eliminate glucose from the body.2 Insulin-treated patients initiated on SGLT-2 inhibitors typically have lower insulin requirements since there is physically less glucose in the body. As a result, patients experience weight loss due to the elimination of approximately 50-100 g of urinary glucose (approximately 200-400 kcal) per day.3 The adverse effect most commonly associated with SGLT-2 inhibitors are genitourinary complications, with greater risk demonstrated in patients with a history of frequent genitourinary infections.4 Selecting the appropriate patients and highlighting the importance of proper personal hygiene and overall cleanliness to patients initiated on these medications may help mitigate the risk of infections and improve the likelihood that patients are maintained on these agents.

Assuming patients’ insurance plans cover these agents and patients are able to afford the copayments, there are a variety of patient factors to consider when choosing between these two drug classes. These include, but are not limited to, desired HbA1c-lowering to achieve patient-specific goals, comorbid chronic conditions, and desire for weight loss. A major consideration to keep in mind is the patients’ amenability to injections. Most GLP-1 RAs are administered subcutaneously, while SGLT-2 inhibitors are oral tablets. Thus, determining if a patient is willing to perform injections is the first step when selecting an agent. Of note, an oral formulation of semaglutide has recently received FDA approval and provides an option to patients who may benefit from a GLP-1 RA, but are not willing to perform injections.5

When considering desired HbA1c-lowering, understanding the comparative efficacies of each class of medications is important. The GLP-1 RAs are associated with a 0.5-1.5% mean decrease in HbA1c, compared to SGLT-2 inhibitors which demonstrated a mean HbA1c-lowering of 0.5-1% in clinical trials.1 Of note, the patients studied in those trials may have been more well-controlled than what is seen in clinical practice; therefore, a more profound effect on glycemic management may be seen. Nevertheless, selecting a GLP-1 RA will generally lead to greater glycemic benefits. Subcutaneous semaglutide, specifically, has the greatest HbA1c-lowering potential of medications in either of the classes and is the preferred agent for patients in whom a significant improvement in glycemic management and weight loss is the main consideration.1

Per the 2020 ADA Standards of Care, for patients with established ASCVD who have already maximized, have a contraindication to, or are unable to tolerate metformin, either a GLP-1 RA or SGLT-2 inhibitor with proven cardiovascular (CV) benefit is recommended.1 These include liraglutide, semaglutide, dulaglutide, for the GLP-1 RAs, and empagliflozin or canagliflozin for the SGLT-2 inhibitor class. Liraglutide and empagliflozin demonstrated a significant reduction in cardiovascular death, and should be among the first agents considered for patients with established ASCVD.6,7 Among patients with high CV risk, these agents are still beneficial for reducing initial CV events and may be considered as well.1

The SGLT-2 inhibitors are the preferred second-line treatment for patients with diabetes with either comorbid CKD or heart failure.1 Their nephroprotective properties and ability to reduce heart failure hospitalizations have been validated in several clinical outcome studies including the EMPA-REG OUTCOME, CANVAS, DECLARE-TIMI and CREDENCE trials.7-10 Additionally, results from the DAPA-HF trial show that dapagliflozin was superior to placebo at preventing the composite endpoint of cardiovascular death and heart failure events, irrespective of diabetes status.11 Historically, SGLT-2 inhibitors were not recommended for patients with an eGFR <45 ml/min/1.73 m2 due in part to subgroup analyses from various trials showing that SGLT-2 inhibitors lose their glycemic-lowering efficacy in patients with advanced CKD.12 However, recent data from the CREDENCE trial demonstrates sustained cardiorenal benefits in patients with macroalbuminuria and an eGFR 30-44 ml/min/1.73 m2, and as a result the ADA has made a recommendation for their use in this population which has since been reflected in the prescribing information for canagliflozin.1,10,13 Alternatively, liraglutide, semaglutide and dulaglutide have all demonstrated more modest renal benefits and can be used in all CKD stages, though liraglutide and semaglutide have not been specifically studied in end-stage renal disease.6,14,15

If weight loss is a goal, both GLP-1 RAs and SGLT-2 inhibitors may be beneficial. GLP-1 RAs have shown more weight loss in clinical trials and in practice.16 Subcutaneous semaglutide offers the most weight loss followed by liraglutide, dulaglutide, exenatide, and lixisenatide.1 Of note, liraglutide is also FDA approved for treatment of obesity as Saxenda® and has a maximum dose of 3 mg daily, compared to Victoza® which is maximized at 1.8 mg daily.1,17 Thus, Saxenda® can be safely used long term in patients looking for weight loss who could also benefit from diabetes management compared to some of the other obesity medications that are only approved for short-term use or have more serious adverse effects.

Other factors that determine whether patients benefit from therapy include the likelihood for adherence and tolerability to the medication. Once-weekly injections, such as dulaglutide, semaglutide, or extended-release exenatide, may be better options in patients with questionable adherence to their current medications or are concerned about pill burden. Additionally, oral agents such as SGLT-2 inhibitors and more recently, oral semaglutide, may be options for patients who have an aversion to regular self-injections. Of note, oral semaglutide must be taken on an empty stomach, 30 minutes before food or other medications, with no more than 120 mL of water to ensure adequate absorption; therefore, despite being a once-daily tablet, these administration nuances may inhibit patients’ adherence to this new GLP1 RA formulation.5 In terms of tolerability, avoiding SGLT-2 inhibitors in patients with a history of frequent UTIs or genital mycotic infections, and avoiding GLP-1 RAs in patients more prone to nausea will limit preventable adherence issues with these medications. Additionally, it is recommended to avoid use of GLP-1 RAs in patients with a history of pancreatitis and personal or family history of medullary thyroid cancer, to avoid these rare but serious adverse effects.1 While reasonable to avoid in patients with a history of pancreatitis, a recent meta-analysis has demonstrated no association between these agents and this severe adverse effect.18

Pharmacological management of type 2 diabetes has shifted to a more patient-centered approach with the recent ADA updates. Considerations including the ones listed above can assist healthcare practitioners in making the most informed decisions when selecting medications.

References

- American Diabetes Association. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes - 2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(Suppl.1):S1-212.

- Dokken, B. The kidney as a treatment target for type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2012;25(1):29-36.

- Rosenstock J, Ferrannini E. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: a predictable, detectable, and preventable safety concern with SGLT2 inhibitors. Diabetes Care. 2015;38(9):1638-42.

- Dave CV, Schneeweiss S, Kim D, et al. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors and the risk for severe urinary tract infections: a population-based cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2019;171:248-56.

- Rybelsus [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk, Inc.; 2019.

- Marso S, Daniels G, Brown-Frandsen K, et al. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(4):311-22.

- Zinman B, Wanner C, Lachin J, et al. Empagliflozin, cardiovascular outcomes, and mortality in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(22):2117-28.

- Neal B, Perkovic V Mahaffey KW, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(7):644-57.

- Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(4):347-57.

- Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:2295-306.

- McMurray J, Solomon S, Inzucchi S, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995-2008.

- Wanner C, Lachin JM, Inzucchi SE, et al. Empagliflozin and clinical outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus, established cardiovascular disease, and chronic kidney disease. Circulation. 2018;137(2):119-29.

- Invokana [package insert]. Titusville, NJ: Janssen Pharmaceuticals, Inc.; 2019.

- Marso S, Bain S, Consoli A, et al. Semaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in patients with type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(19):1834-44.

- Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, et al. Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): a double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:121-130.

- Burcelin R, Gourdy P. Harnessing glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists for the pharmacological treatment of overweight and obesity. Obes Rev. 2017;18(1):86-98.

- Saxenda [package insert]. Plainsboro, NJ: Novo Nordisk, Inc.; 2019.

- Monami M, Dicembrini I, Nardini C, Fiordelli I, Mannucci E. Glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists and pancreatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2014;103(2):269-75.