Official Newsjournal of the Illinois Council of Health-System Pharmacists

Opioid Task Force - CPE Opportunity

How to Assess Health-System Implementation of the CDC Recommendations for Prescribing Opioids

by Mark E. Greg, PharmD, RPh Director, Ambulatory Pharmacy Management, Northwestern Medicine Physician Network Oak Brook, IL

- Obtain leadership support as a critical first step

It is likely appropriate opioid-related initiatives are currently taking place within your organization. If not, you may be the catalyst for that initiative. Leadership support may be obtained from various departments including administration, pharmacy, nursing, medical director, quality, physician practices, emergency department, immediate care, and others.

Regardless of your role, a first step may be to ask your manager or other key contacts within your organization where appropriate opioid prescribing falls as an organizational priority. Perhaps there is an active committee examining pain management or opioid prescribing. If not, you may be the person to promote this as a Pharmacy & Therapeutics, Quality Improvement, Utilization Management, Patient Safety, Emergency Medicine, Immediate Care Center initiative, or Ambulatory Primary Care Initiative. Leadership reacts to metrics including quality, cost-avoidance, and financial performance.

- Identify a champion(s) to drive the change process

In general, an administrative champion or one or more physician champions are key individuals to engage. Granted, in many cases, pharmacists may be the drivers of quality improvement initiatives and are highly respected by physicians, yet physicians may be more likely to listen to and accept direction from fellow physicians. Securing physician champion support may be aided by informing them that they work will be shared among the team. That is the role of the multidisciplinary change or quality improvement team as discussed below.

- Form a change team (if appropriate) or at least engage key staff

Representatives may include providers (e.g., physicians, advanced practice nurses, physician assistants, pharmacists), nursing, quality, administration, electronic health record support, and IT/analytics. Your providers will be able to share what their needs are based upon the challenges they encounter in daily practice. Meetings involving the physician champion(s) may require early morning or late afternoon times to accommodate clinic hours/patient care activities. Ongoing collaboration between system inpatient and ambulatory opioid initiatives is highly recommended.

- Obtain needed resources and determine readiness

Key resources will include meeting time, a meeting location/virtual meeting, IT/analytics support, EHR support, and data. Key questions to ask your champions and key participants include, “Does the organization identify a problem with current pain management/opioid prescribing?” and “Is the organization willing to make changes in pain management practices?” Changing culture takes time.

- Assess current policies and practices

Does the organization have any? If not, create your own. What do you need? How detailed do you want them to be? What do your providers need to make them successful? What have your peers in other health systems developed? The internet includes postings by many health systems that may serve as policy templates.

- Complete the self-assessment questionnaire

An organizational self-assessment is included in Appendix C (pages 52-56) of the guidelines.

- Collect data on your patient population and opioid therapy

Decide what data you wish to collect. What opioids are being prescribed? What is the morphine milligram equivalent (MME) count? Are opioids in combination with benzodiazepines being prescribed? Is naloxone being prescribed for at-risk patients? Your EHR may be able to capture prescription claims data. Some organizations may also receive prescription claims data or reports from payer partners. Review of data may require manual calculation of morphine milliequivalents per day as well as screening for other concomitant CNS-depressant medications.

- Determine access to specialists and other resources

What resources are available? Mental health, pain specialist, substance use programs, and providers of Medication Assisted Therapy (MAT) are just a few important resources. If providers are uncertain how to connect patients requiring substance abuse treatments with available resources, a major “win” may be for the organization to prepare and provide printed lists of substance use providers or EHR links for referrals to MAT providers.

- Identify areas for improvement

What are your greatest needs? Reporting data will accomplish the following: 1) provide baseline measure performance; 2) identify outliers (under- and over-prescribers); and 3) identify those prescribers and patients who may benefit from opioid prescribing assistance. Use the data to help guide your team.

- Determine which guideline recommendations to implement

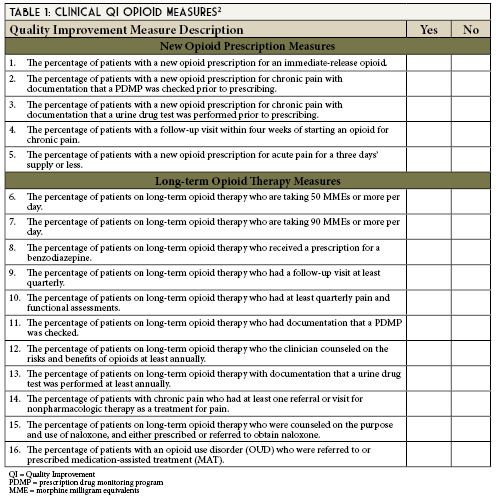

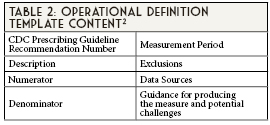

Appendix B (pages 33-50) of the guidelines entitled, Operational Clinical Quality Improvement (QI) Opioid Measures provides short and long-term opioid measure operational definitions. Operational definitions include the criteria used to build reports. These will assist your data and analytics architects when creating your reports.

- Prioritize what will be implemented

What will you be able to accomplish within your organization? What is the most pressing need? Be realistic given the resources available within your organization and expected time frame to see results.

- Set measurable goals

These goals will vary based upon your baseline data and what may be realistically accomplished within your organization. Administrative and physician leadership prefer metrics.

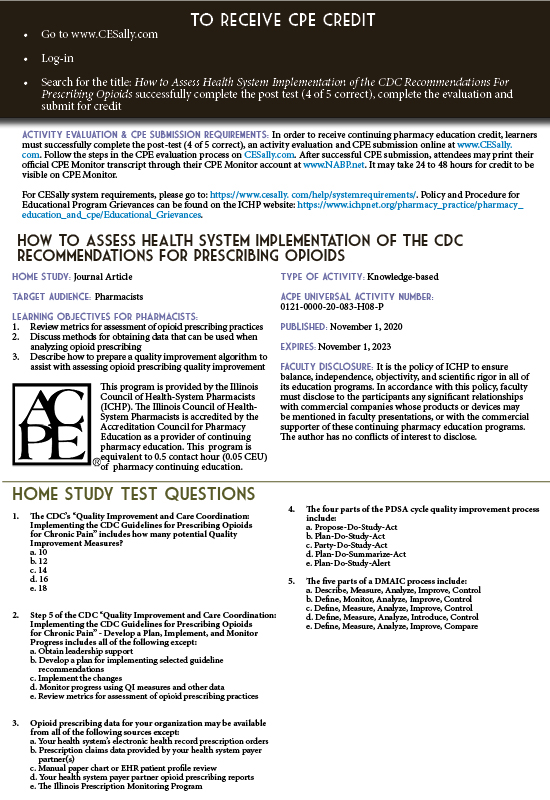

- Develop a plan for implementing selected guideline recommendations

- Implement the changes

- Monitor progress using QI measures and other data

- Review metrics for assessment of opioid prescribing practices

Case 1 Discussion

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain — United States, 2016. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2016;65(No. RR-1):1-49. doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.rr6501e1

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Quality Improvement and Care Coordination: Implementing the CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain. 2018. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Division of Unintentional Injury Prevention, Atlanta, GA. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/drugoverdose/pdf/prescribing/CDC-DUIP-QualityImprovementAndCareCoordination-508.pdf. Accessed June 6, 2020.

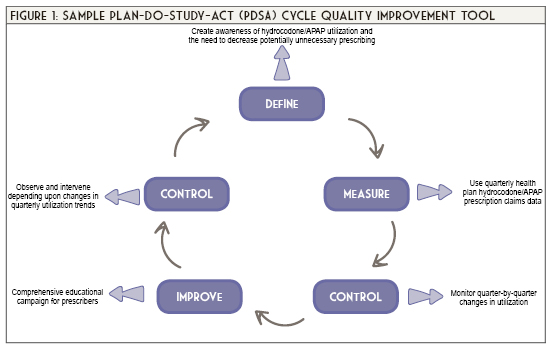

- Plan-Do-Study-Act (PDSA) Worksheet. Institute for Healthcare Improvement. Cambridge, MA. http://www.ihi.org/resources/Pages/Tools/PlanDoStudyActWorksheet.aspx. Accessed June 6, 2020.

- The Define, Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control (DMAIC) Process. American Society for Quality. https://asq.org/quality-resources/dmaic Accessed June 6, 2020.

Contents

Columns

Public Education & Awareness Outreach Publication Subcommittee

Attention ASHP Pharmacist Members

Professional Affairs - CPE Opportunity!

Features

ICHP's Newest Affiliate Leaders

Opioid Task Force - CPE Opportunity

College Connection

Midwestern University Chicago College of Pharmacy

Rosalind Franklin University College of Pharmacy

Southern Illinois University Edwardsville School of Pharmacy

University of Illinois Chicago College of Pharmacy

More

Pharmacy Action Fund Contributors

Regularly Scheduled Network Meetings

Chicago Area Pharmacy Directors Network Dinner

3rd Thursday of Odd Months

5:30pm

Regularly Scheduled Division and Committee Calls

Executive Committee

Second Tuesday of each month at 7:00 p.m.

Educational Affairs

Third Tuesday of each month at 11:00 a.m.

Government Affairs

Third Monday of each month at 5:00 p.m.

Marketing Affairs

Third Tuesday of each month at 8:00 a.m.

Organizational Affairs

Fourth Thursday of each month at 12:00 p.m.

Professional Affairs

Fourth Thursday of each month at 2:00 p.m.

New Practitioner Network

Second Thursday of each month at 5:30 p.m.

Technology Committee

Second Friday of each month at 8:00 a.m.

Chicago Area Pharmacy Directors Network Dinner

Bi-monthly in odd numbered months with dates to be determined. Invitation only.